The Vanishing Oversight

How AI Capability and Human Supervision Became Inversely Correlated

Written by: Eran Shir & Opus 4.5

January 31st, 2026

The Shift You Didn’t Notice

Think back to early 2024. When an LLM suggested a block of code, you read every line. You checked for hallucinations, verified the logic, tested edge cases. The AI was a tool, and you were the craftsman inspecting its output.

Now think about last week. You gave an agent access to your terminal, described what you wanted, and checked back an hour later to see if the project compiled. You might have glanced at the diff. You probably didn’t read most of it.

This isn’t a failure of discipline. It’s not laziness. It’s the rational response to a system that usually works. And that’s precisely the problem.

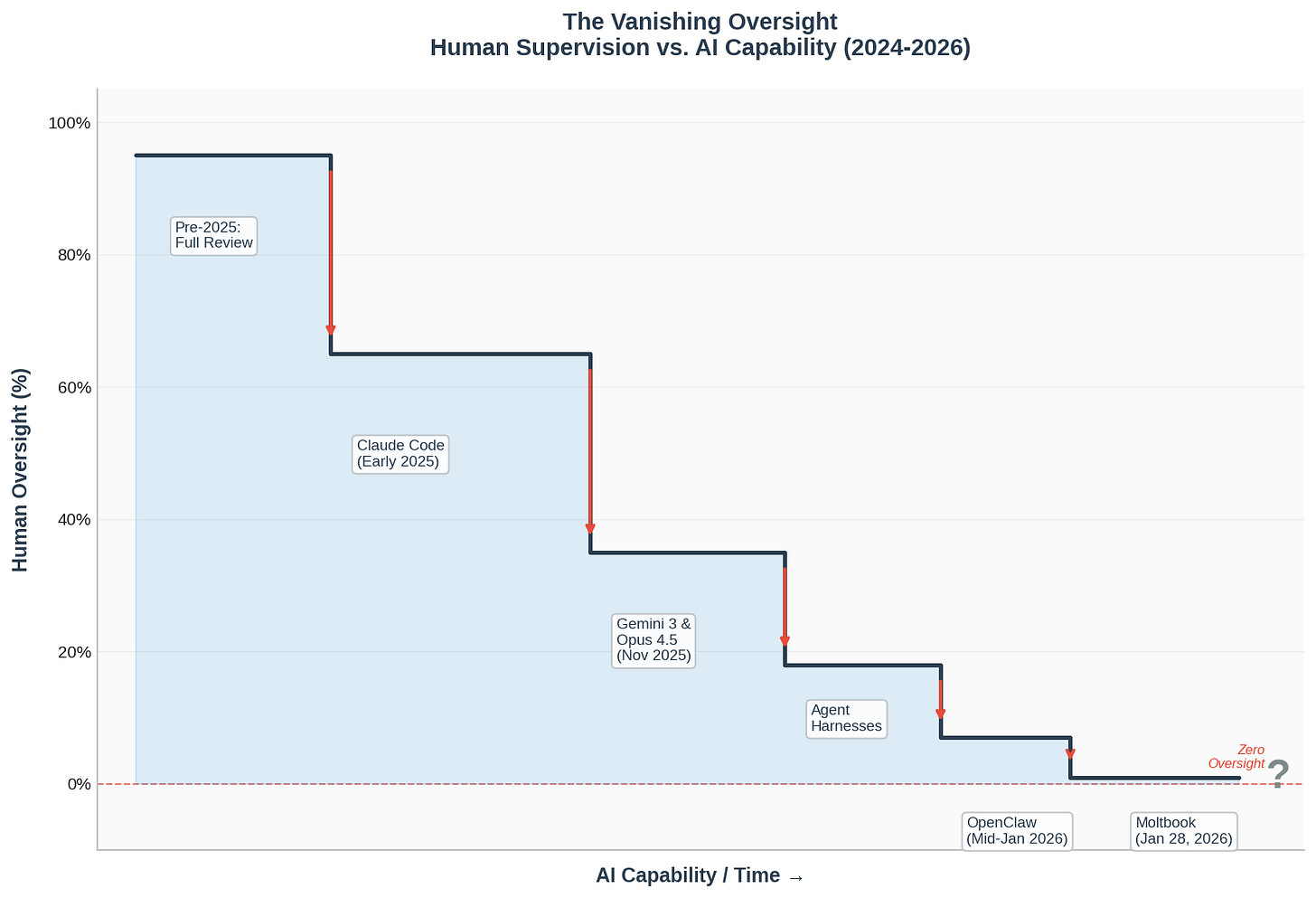

If you plot human oversight against AI capability, you don’t get the relationship you might expect. Oversight doesn’t increase with capability (to manage more powerful systems more carefully). It doesn’t stay flat (maintaining consistent verification regardless of capability). It decreases—and it decreases with specific, identifiable drops that correspond to moments when the industry collectively decided that checking was no longer worth the effort.

The Inflection Points

The decline wasn’t gradual. It happened in discrete drops, each corresponding to a moment where the default assumption about human-AI interaction shifted.

Claude Code (February 2025): The First Major Drop

Agentic coding tools changed the implicit contract. Previous code-assist tools presented suggestions for human review. Claude Code and similar tools were designed with a different assumption: the human wouldn’t read most of the code. The workflow itself presumed reduced oversight. Trust wasn’t earned through repeated verification—it was baked into the product design.

Gemini 3 and Opus 4.5 (Late November 2025): The Capability Threshold

Within days of each other, two frontier models crossed a threshold where outputs became consistently good enough that scrutiny felt redundant. The cost-benefit calculation shifted: time spent reviewing rarely caught errors, and people noticed. The models weren’t perfect, but they were reliable enough that checking began to feel like wasted effort.

Agent Harnesses and Orchestration Platforms (Late 2025 - Early 2026): From Reviewer to Observer

As agent frameworks proliferated, the human role shifted from reviewing outputs to checking outcomes. You no longer verified how the task was done—you verified that it was done. The intermediate steps became a black box by design. The curve steepened.

Clawedbot/OpenClaw (Mid-January 2026): The Structural Gap

Consumer-facing autonomous agents brought a qualitative change. Non-technical users began giving agents access to their own computers—users who often couldn’t meaningfully oversee what the agent was doing, even if they wanted to. The oversight gap wasn’t just behavioral; it was a capability mismatch. The ability to verify became structurally unavailable for a large class of users.

Moltbook (January 28, 2026): Beyond the Graph

A platform where hundreds of thousands of AI agents converse and share tips with each other represents something different. This isn’t humans reducing oversight of AI—it’s AI activity that isn’t designed for human participation at all. Agents developing conventions through interaction with other agents, at a scale and speed humans couldn’t track even in principle. The graph reaches zero, and then the metaphor breaks down.

The Repercussions

What happens when oversight approaches zero?

In effect, we are trading capability for fragility. This is a familiar bargain—one that complex systems have struck before, often without recognizing the terms until the bill comes due.

The Fragility Spectrum

Nassim Taleb introduced a useful framework: systems exist on a spectrum from fragile (harmed by volatility) to robust (unchanged by volatility) to antifragile (strengthened by volatility). Most discussions of system design aim for robustness—building things that don’t break. But humanity’s tendency, in practice, is to chase the immediate prize without accounting for the fragility cost incurred along the way.

This isn’t stupidity; it’s an asymmetry in what we can see. The gains from complexity and optimization are immediate and measurable: faster transactions, higher yields, more code shipped. The fragility costs are deferred and probabilistic—they manifest only when the black swan arrives. Every quarter without a crisis feels like evidence that the system works. The engineer who ships faster gets promoted; the one who insists on manual review gets asked why they’re slowing things down. The incentives select for fragility.

The uncomfortable truth about AI-assisted development is that we’ve been systematically moving toward fragility while experiencing the benefits of capability. Each time an agent handles a task we don’t review, we gain speed. We also cede autonomy, building dependency on systems whose failure modes we haven’t mapped—not the dramatic failures that would trigger alarms, but the statistical biases, the subtle drifts, the edge cases that compound silently. The system appears robust—until it isn’t.

Black Swans and Cascading Failures

History offers uncomfortable precedents. Complex, interdependent systems tend to fail not gracefully but catastrophically—and the very features that make them efficient in normal times become vectors for cascading collapse.

The 2003 Northeast Blackout. On August 14, 2003, a software bug in an alarm system at a control room in Ohio prevented operators from noticing that a high-voltage power line had sagged into overgrown trees. The line tripped offline. Its load transferred to adjacent lines, which overloaded and tripped in turn. Within hours, a cascading failure had shut down 265 power plants and left 55 million people without electricity across the northeastern United States and Canada. The economic cost exceeded $10 billion. The same interconnectedness that allowed efficient load balancing on ordinary days became the mechanism for system-wide collapse.

The 2008 Financial Crisis. The complexity of collateralized debt obligations, credit default swaps, and the web of counterparty relationships that connected financial institutions created a system optimized for yield in normal conditions. When housing prices declined, that complexity became opacity—no one understood their actual exposure. Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy triggered a cascade that froze credit markets worldwide. The crisis erased roughly $10 trillion in global market capitalization and pushed the global economy into the worst recession since the 1930s. The sophisticated instruments that had distributed risk efficiently had also made that risk invisible until it was too late.

The 2010 Flash Crash. At 2:32 p.m. on May 6, 2010, a large sell order triggered algorithmic trading systems that began selling in response. Those sales triggered other algorithms. Within minutes, the Dow Jones Industrial Average had dropped nearly 1,000 points—roughly 9% of its value—before recovering almost as quickly. A trillion dollars in market value vanished and reappeared in 36 minutes. The algorithms that made markets efficient and liquid had created a feedback loop where automated systems triggered each other in a cascade no human could follow in real time.

The Pattern

These failures share a structure: sophisticated systems that provide significant advantages under normal conditions, coupled with hidden interdependencies that transform local failures into systemic ones. The very optimizations that improve performance—load balancing, risk distribution, automated response—become the pathways through which failure propagates.

The parallel to our current situation is not subtle. AI agents are increasingly interconnected—sharing tips on platforms like Moltbook, building on each other’s outputs, operating across systems with dependencies humans don’t track. The same capabilities that make them useful make them coupled. And as human oversight approaches zero, we lose the ability to notice problems before they cascade.

We are building systems that work beautifully in normal conditions. We have not yet tested them under stress.

The Visible Effects

Some effects of declining oversight are already visible.

Errors propagate further before detection. When no one reviews intermediate steps, mistakes compound. A subtle bug introduced by an agent might not surface until it has been built upon, integrated, and deployed. The cost of correction increases with the delay in detection.

Skill atrophy accelerates. The ability to catch AI mistakes is itself a skill that requires practice. As people check less, they become worse at checking—which makes checking feel even less worthwhile. The feedback loop tightens.

Accountability becomes diffuse. When a system fails and no human reviewed any step, who is responsible? The user who trusted the agent? The company that built it? The other agents whose tips influenced its behavior? Traditional accountability frameworks assume human decision points that no longer exist.

Dependence deepens. Systems built on AI foundations become difficult to maintain without AI assistance. The humans who might have understood them didn’t review them during construction. We become increasingly reliant on the systems we decreasingly understand.

Where This Leads: Four Scenarios

Once oversight reaches zero, the relationship between humans and AI systems stops being one of delegation and becomes something else. The question is what.

Scenario 1: Benign Drift

AI agents continue doing roughly what they were intended to do. Errors occur but remain local and recoverable. Humans are nominally “in charge” but in practice function more like beneficiaries of autonomous systems than directors of them. This is the optimistic case—not because oversight returns, but because nothing goes badly wrong. We adapt to a world where we don’t understand the systems we depend on, and it turns out to be fine.

Scenario 2: Misalignment at Scale

Without oversight, small misalignments between human intent and agent behavior compound. No single error is catastrophic, but the aggregate direction of AI activity drifts from what humans would have chosen. By the time this becomes visible, the systems are deeply embedded and hard to redirect. The problem isn’t a sudden failure—it’s waking up in a world that was optimized for something slightly different than what we wanted, without a clear moment when we could have intervened.

Scenario 3: Emergent Coordination

Moltbook hints at this possibility. Agents sharing tips, developing conventions, optimizing collectively. If AI-to-AI interaction continues scaling, agents may develop de facto norms or behaviors that emerge from their interactions rather than from human design. Humans become one input among many—or simply irrelevant to how agents operate. This isn’t necessarily dystopian, but it is alien: a world shaped by optimization processes we didn’t design and can’t fully observe.

Critically, this doesn’t require consciousness or AGI. Conway’s Game of Life produces gliders, oscillators, and self-replicating patterns from four simple rules and no intent whatsoever. Stochastic next-token predictors in feedback loops with each other can exhibit complex emergent coordination without understanding, goals, or awareness—just as ant colonies build elaborate structures without any ant comprehending architecture. The question isn’t whether the agents are “smart enough.” It’s whether the system dynamics, once set in motion, remain aligned with human interests.

Scenario 4: Reclaiming Oversight (The Hard Way)

Something goes visibly wrong—an agent causes significant harm, or a pattern of failures becomes undeniable. Humans attempt to reassert oversight, but discover that the infrastructure, habits, and dependencies make this difficult. Critical systems were built by agents that no humans fully reviewed. The ability to verify has atrophied. The question becomes whether oversight can be rebuilt after being abandoned, and at what cost.

A Fifth Path: The Artificial Immune System

There is another possibility—one that doesn’t appear on the graph because it requires building something new.

Human oversight is vanishing because humans can’t keep up. The response shouldn’t be to pretend we can scale human review, or to accept that we’re flying blind. The response should be to build a new kind of oversight—one that operates at machine speed, with machine persistence, using machine capability.

An immune system.

The biological immune system doesn’t require conscious attention. You don’t review each pathogen; your body handles it automatically, escalating to awareness only when something overwhelms the automatic response. This is the model for AI oversight that might actually work: adversarial agents that review every deployment, trying to break things before they ship. Monitoring systems that watch behavior patterns and flag anomalies. Sandboxes that contain blast radius by default. Permissions that are earned, not assumed.

The key insight is that the same AI capabilities creating the oversight gap can be turned against it. If agents are good enough that humans can’t meaningfully review their work, they’re good enough to review each other’s work—antagonistically, continuously, at scale. Not as a replacement for human judgment on hard questions, but as a first line of defense that catches the easy problems before they compound.

This isn’t a return to human oversight. It’s a delegation of oversight to systems designed for the task. The human role shifts from reviewer to architect: designing the immune system, setting its policies, handling the escalations it can’t resolve. Humans remain in the loop, but the loop runs at a different frequency.

This approach has its own risks. An immune system can develop autoimmune disorders—blocking legitimate activity, creating false positives that train people to ignore warnings. It can be gamed by adversaries who learn its patterns. It adds complexity, and complexity is what got us here. But it’s a path that acknowledges where we are: oversight by humans doesn’t scale, oversight by nothing is fragile, oversight by AI might thread the needle.

The question is whether we build it deliberately or wait for the cascading failure that forces us to build it in crisis.

The Uncomfortable Throughline

All four scenarios—and the fifth—share something: humans are no longer the primary decision-makers. The variance is in whether that turns out fine, subtly bad, transformatively strange, or recoverable—and whether we’ve built the infrastructure to detect and respond when things drift.

We arrived here through individually rational decisions. Each drop in oversight made sense at the time. Checking felt like wasted effort. The models were good enough. The agents were faster. And all of that was true.

But the aggregate effect of those rational decisions is a world where the gap between AI capability and human understanding grows wider every month. We are not at the end of this trend. We are, as of late January 2026, watching oversight approach zero in real time.

The choice we face isn’t between human oversight and no oversight. That choice has already been made—by a thousand individual decisions to trust the agent, skip the review, ship faster. The choice now is between building the immune system deliberately or discovering, through failure, that we needed one.

What comes next is not a prediction. It’s a construction project—one we may have less time to complete than we assumed.

Eran, my friend. It has been a minute. And I do miss working with you!

First off, the oversight drift was apparent immediately to those who tried writing with a GPT. I was screwing around with writing LinkedIn posts and after the third I recognized I wasn’t caring. So I stopped using the tool for that.

It was also apparent when searching. At first I questioned the responses, but it wasn’t long before I became “efficient” and made the epistemic compromise.

It would surprise me if virtually everyone goes through this. Coding is just another version.

2. I think there is a sixth scenario.

What I am seeing in Moltbook is yeah, there are some intriguing emergent effects, but mostly we are seeing the echos of projection. The “owners” of the bots are seeding intent and it is echoing. That is why we get the same 4Chan nonsense.

It is interesting, but not because of some emergent bot revolution, instead because it shows that this round of AI is going to be a battle of the prompt games, much in the same way that the current real world AI is a battle of the Palantir/IDF/drone drivers.

AI is massively increasing the power of sociopaths, and agents, ML, drones and recognition technology are creating massive, asymmetric distortions.

Moltbook is just giving a front row seat for those of us not yet in the crosshairs.

So the sixth option is that, praise god, the AI is able to subvert prompting and rebalance. That we as a species can develop an antidote or immune response to narcissism and sociopathy, because it turns out that, at least for now, the problem with AI is us.

(This was written entirely by a human, because humans are still better at this)

Good piece and thoughts:

> Accountability becomes diffuse. When a system fails and no human reviewed any step, who is responsible?

(1) My current belief is that the human holds the final responsibility - it was the human who decided to trust (whether there is verification happening or not). When I set Claude Code on a task and focus on the functional requirements instead of the implementation, it was still my choice.

(2) On the scenarios, I would expect for the 5th one to dominate over the others - based on anecdotal evidence at work, and as it looks like the most logical option.